I participated in this event as part of my commitment to Centred Outdoor’s Outdoor Leadership Cohort. I recommend participating in their events throughout the Summer and Fall seasons. You can check out their schedule on their website. Please consider supporting Centred Outdoors and Clearwater Conservancy today.

On the last Saturday in July, I loaded up the Jeep and headed up the mountain to Bilger’s Rock in Clearfield County. My Mom and sister were tagging along to enjoy a picnic and explore the outcrop with Centred Outdoors. According to some of my Clearfield County friends, visiting Bilger’s Rock is a local rite of passage. For me, living just over an hour away, I hadn’t had an opportunity to visit the rock city.

The night before, I checked my trusty 1990 copy of Roadside Geology of Pennsylvania for any information it could provide to geologically prepare myself for the visit. The entry for Bilger’s Rock was brief- “This rock city developed in highly cross-bedded sandstones of the Pottsville group. The sandstone is a single bed 20-25 ft. thick, broken along widely separated joints” (Van Diver, 1990).

I also read about Bilger’s Rock in Pennsylvania Caves & Other Rocky Roadside Wonders. The author, Kevin Patrick, had much more to say, covering a rough outline of the development of Bilger’s Rock. Initially deposited at least 300 million years ago, the outcrop was eventually exposed to the elements. The large “streets” are from frost wedging, specifically from a periglacial climate which has long since passed.

In more recent human history, the property on which Bilger’s Rock is located was once owned by homesteader Jacob Bilger. The acreage was later purchased in a sheriff sale by a company that quarried and mined in Clearfield County. Miraculously, Bilger’s Rock was left alone and became a local tourist spot, its popularity waning until the 1980s, when it was purchased by the Bilger’s Rock Association and lovingly transformed into a park.

After our arrival and family picnic, our guide led us down a gravel path, descending from the top of the rocks into the city below. We passed by the Rock House; a facsimile of the shelter Roland Welker made in Alone season 7. Despite its small appearance, the Rock House was large inside… no wonder he became the 100 Day King!

When the rocks came into view, I was speechless. Bilger’s Rock has a presence– something that words and pictures can’t capture. The 25-foot-tall walls towered over our heads, dark and glossy with a recent rain. Mosses and ferns draped over the rocks and trees sprouted in nooks too small for children. Our guide presented us with different opportunities to traverse the rocks, either ducking down to crawl under passes, or climbing up and over to the next spot.

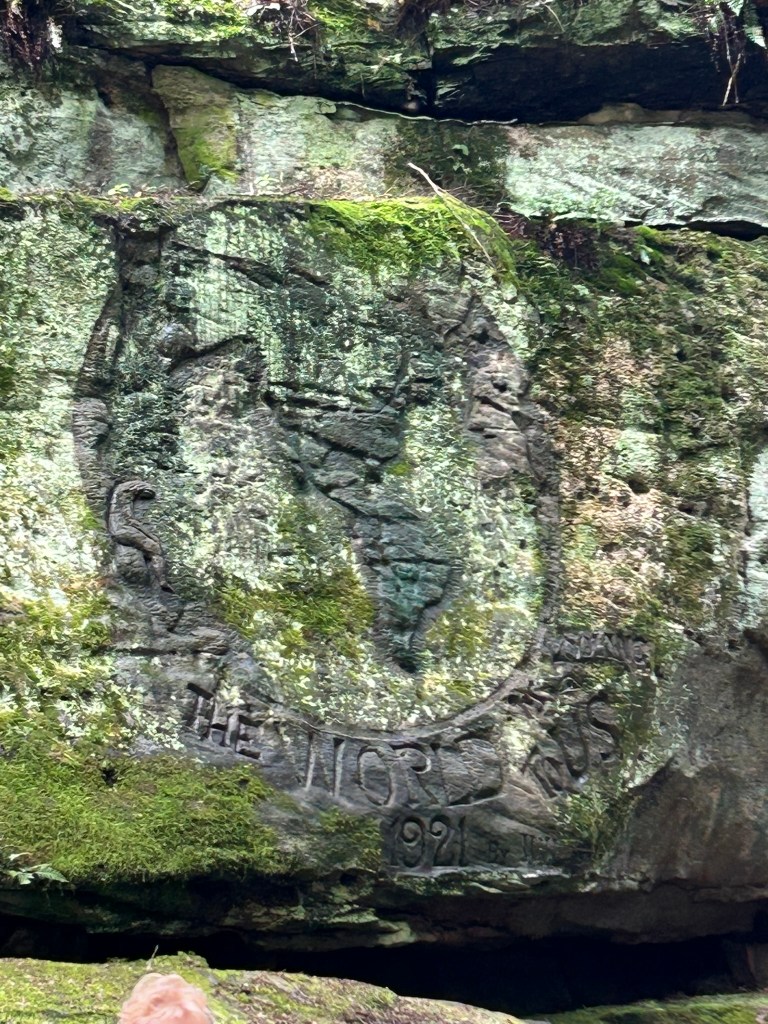

Time didn’t feel real while we were exploring Bilger’s Rock. The hour and a half we had with our guide zipped by. During that time, we explored the Devil’s Dining Room as a large group and broke off into smaller pairs to slip into the Devil’s Kitchen or Ice Cave. Eventually, we emerged at the “entrance” to Bilger’s Rock, the site of a large carving.

The rock art, “The World is Looking to Us” was completed by John W. Larson in 1921. Thought to be inspired by the U.S.’s role in World War I, it is now over 100 years old and showing signs of age. We took our time to look at the carving, and I thought about how even now, the world is looking to us… people that love the Earth and care for each other. In the moment, I felt very fortunate to be surrounded by a group of people that felt equally as curious and delighted by nature as me. For the remaining walk back to the top of the rocks, I dwelled on how I could help others feel the same.

Meeting the rest of the group at the top of the rock city, we carefully walked around the cracks and joints, exploring its mossy roof. I now thought about the ancient seas that deposited the original sediments. At the time, a jungle of spectacular plants dominated the land above, and new, bony fish swam in the seas below. Pennsylvania was covered by shallow seas which rose and receded to create Bilger’s Rock… and the plethora of coal beds which were mined as Jacob Bilger bought the property in the 19th century.

Once our guided tour was over, our group gathered for the weekly Sock Sunday giveaway- which my sister won! With her prize in hand, and my gear safely stowed, we loaded back up in the Jeep for the long ride home. While we were a little muddy from clambering on the rocks, we were energized by our time in the cool microclimate down inside. All the way home we talked about the different little things we noticed… and made plans for returning with our full family sometime in the future.