A Red-Tailed Hawk swooped down through the trees, alighting a branch to watch students. I was there, too- walking through Hort Woods after lunch with my colleagues. It’s been a while since I saw a hawk on campus, and years since I’ve been near to my favorite bird.

In parts of medieval folklore, witches had something called a familiar– a supernatural creature meant to guide them through their use of magic. Red-Tailed Hawks are my familiar, always appearing at unusual moments to call my attention to the world around me. When I was fifteen, I had a close call with a Red-Tailed Hawk while refilling the feeders in my parents’ yard during my morning chores. While shimmying the barrel of a feeder up its string, a soft whump sounded from behind me. A chill crept up my neck as I turned- I’m terrified of bears- only to find a Red-Tailed Hawk deep in the snow. She had most likely seen prey in the yard and dived for it, not minding the awkward teen bumbling about the yard in her snowsuit.

This type of experience has been repeated… once, when I was nineteen, I spotted a hurt Red-Tail alongside the road and called it in to the Game Commission. I waited there, directing travelers until PGC came to pick up the bird. Again: at twenty-six I was talking on the phone in the courtyard when a Red-Tail decided to take a seat on the brick wall nearby with its lunch.

Fear is not a part of a Red-Tailed Hawk’s vocabulary. When mated, Red-Tails will guard their territory together from other Red-Tails and predators. If a human strays too close to their nest, a Red-Tail will take no qualm in attempting to scare them away. I ‘ve seen hawks diving cross-traffic to hit prey in a grassy median. Along I-99, they perch on the fencing while PennDOT rumbles by in the mowers.

The two Red-Tails I see on my daily commute are road warriors. The hills between Bellefonte and State College are perfect hunting grounds. A huge swath passes through SCI Rockview and Penn State research farms. The regularly cultivated fields help form thermals necessary for hawks to travel. Plus, there’s a sprinkling of Wildlife Management Units, permitting nature to live unimpeded.

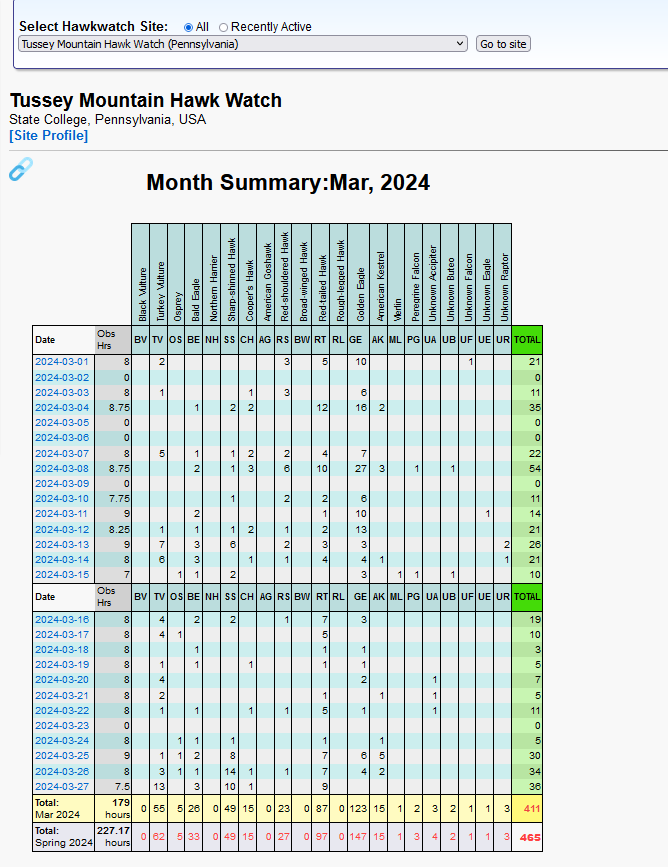

The intersection of human beings and wild raptors is increasingly in favor of human beings- but there are people trying to change the outcome. I recently learned about the Tussey Mountain Spring Hawkwatch, which has spotted 97 Red-Tails during 227 hours of watching. Programs like these provides important data used to build population and migration models. Simply watching and noting where and when we are seeing Red-Tails, we are contributing to the body of knowledge that is trying to provide a better understanding of our wild neighbors.

I noted my on-campus Red-Tail in eBird, briefly delaying our march back to the office. However, as soon as it was spotted, the hawk was gone, too quick for a photograph. I explained to them the importance of my stop and showed them my app- and continued our walk, as if nothing was out of the ordinary. The moment was extraordinary for me, as my familiar crossed my path and instructed me to pay attention.